WGA and SAG-AFTRA's Fight for Fair Residuals

WGA and SAG-AFTRA remain in a deadlock with film and television producers. Chief among the reasons for the ongoing strikes are low residual payments from streaming service providers.

With streaming services being a rapid source of films and series, the writers and actors working for them deserve compensation for their projects. However, the structure of streaming services upends the formulas that have historically calculated residuals. The strikes could represent the need for a significant change in how residuals are given out.

How are low residuals affecting writers and actors?

The majority of actors working in America have to get other jobs to support themselves. As for writers, they’re steadily employed for as long as a film or series is in production, then have to find another job.

Residuals were developed in 1960 to compensate motion picture staff for screenings of their films on television. They are typically calculated based on many factors: the budget of a production, the size of a worker’s role and how the film/show was viewed.

Streaming services, however, typically pay writers and actors a flat rate that’s previously been set by those workers’ respective unions. The popularity of a program on a streaming service hardly translates to high residuals.

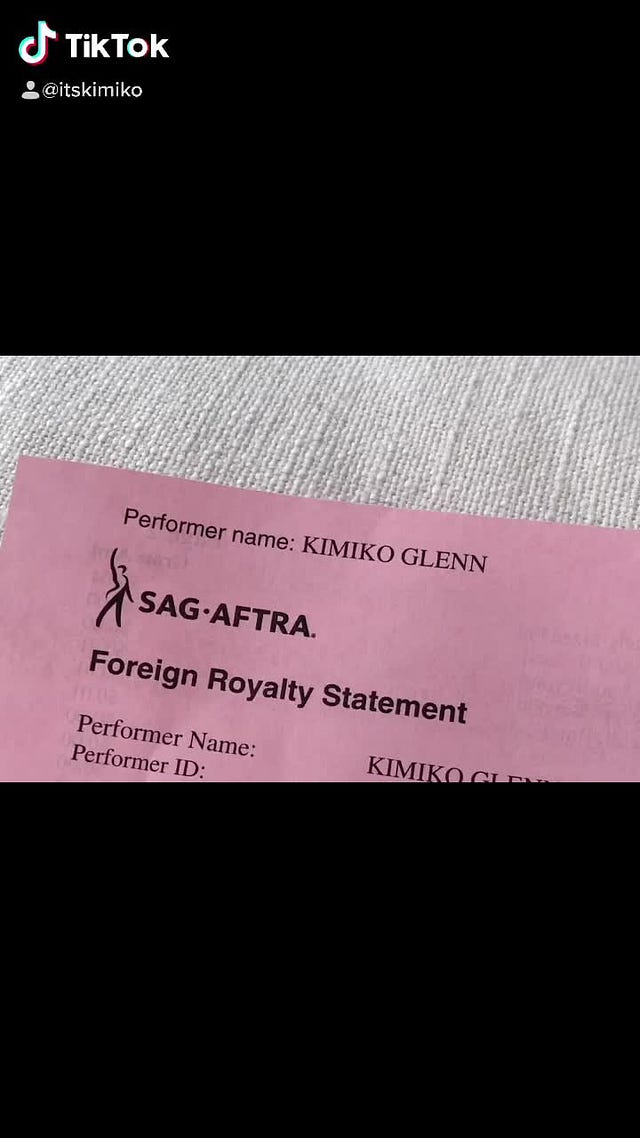

Kimiko Glenn, an actor on the popular Netflix original series Orange is the New Black, famously posted a TikTok video of her opening a residual cheque for the series. She only received a paltry $27.30 for international streams of a whole season of her series.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Kimiko Glenn shows her international residuals for OItNB, kimiko (@itskimiko), Official | TikTok

Glenn went on to share in a later post that it was common for actors on OItNB to work second jobs and that not even their upfront payments were very high.

Writers, meanwhile, find themselves with shorter seasons to work on. A standard broadcast television season has 22 episodes, but an average season of a Netflix original has 8 or 10 episodes. Not only does this mean less pay-by-hour, but it’s also led to a trend in streaming series production called mini-rooms.

Mini-rooms are where an established showrunner and at least two more writers must devise scripts for two or three episodes of a potential series. They efficiently produce two or three more scripts beyond the pilot before a series is even greenlit.

WGA has spoken out against mini-rooms because they make it hard for newer writers to get established in the industry. If a series is given a full season, the additional writers who were employed in the mini room aren’t typically employed in the full series’ writing staff. They are only paid by scale and are given fewer weeks of work than a traditional TV writers’ room.

Why aren’t writers and actors fairly compensated?

Residuals for streamed content are smaller because there’s no way to effectively measure the ‘success’ of a program.

When a product is rereleased in cinemas, a percentage of box office revenue is used to calculate fair residuals for the cast and crew’s work. For TV broadcasts, including reruns, Nielsen ratings are used to calculate residual percentages. Streaming services, however, receive revenue from subscriptions.

Streaming services, however, are a subscription-based service. Their revenue stream is tied to whatever tier a viewer is subscribed to. That makes it difficult to calculate how much money the streaming services owe the cast and crew of a film or series.

The production management assistant service Entertainment Partners came up with a formula to help companies determine residuals for streaming services. New high-budget content, which makes up 75% of Netflix’s output, is a union flat rate multiplied by a predetermined rate that diminishes annually.

This pays workers residuals that presume a high-budget show is successful. Those predetermined rates, however, don’t account for the budget and number of views on a film/series, as traditional residuals would. Streaming services are known to collect data on how many views something gets, but they are notoriously tight-fisted about sharing that data publicly.

Creatives aren’t paid accurately for their contribution to a streaming service. They also can’t argue against low residuals without proof of how many people saw their product.

The only thing that can be predicted as essential data is how many new subscribers a streaming service gets. A Bloomberg report revealed that Netflix prioritises new subscribers or people who don’t watch frequently over binge-watchers. That priority makes sense for increasing revenue from subscriptions.

But writers and actors aren’t told whether their shows drive subscriptions. Streaming services are known for cancelling series, or even finished products, without explanation. The lack of transparency between workers and streaming service providers makes it difficult to argue for a worker’s right to higher residuals.

The residual model needs to change

On July 12, SAG-AFTRA walked away from negotiations with the Association of Motion Picture and Television Producers when the latter refused their proposal for sharing in revenue “earned by the streaming service.” The AMPTP responded with a claim that they can’t give actors streaming service revenue because that money is not given to producers of films and series either.

That justification reflects how the current residual system isn’t sufficient for streaming products. Residuals were introduced because of a shift in the industry: the introduction of television. But the television landscape has been disrupted by streaming services. The continued striking could be a sign that another structural change is needed.